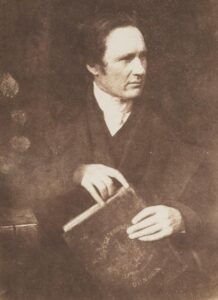

Mackintosh Mackay, Dunoon

Dr Mackay the was born in the parish of Eddrachillis, Sutherland. His father rented the farm of Duartbeg and was a captain in the Reay Fencibles. He was an amiable man, and a pious Christian of superior intelligence and a consistent life. His mother was the eldest daughter of Rev Alexander Falconer, minister of Eddrachillis. She was an admirable woman, of a loving, cheerful disposition, a delightful companion, a wise and sincere friend, a devoted wife and mother, and an intelligent and devout Christian. Their son Mackintosh was born in November 1793.

After receiving an elementary education at home, his studies were then conducted in the parish school of Tongue and afterwards in an academy at Ullapool, conducted by a Mr Pollock, who was competent so to ground him in Greek and Latin and Mathematics as to enable him to follow a course of instruction in the University of St Andrews. Few young men from the far North ever entered college better able to take a prominent place than Mackintosh Mackay, with his unusual talent, his opportunities of preparation, his devotion to study, his capacity for enormous labour, and his conscientiousness in any work which was given him. He was not too young when he entered college in 1815.

In 1820 he entered the theological hall at Glasgow. It was there chiefly his theological studies were conducted, but he attended “partial sessions” both in Edinburgh and Aberdeen. During the recess between his college sessions, he was employed as a teacher successively at Bowmore, Laggan and Portree.

He was licensed to preach in 1827, and in the following year was ordained and inducted as parish minister of Laggan. While there he completed his work as editor of the Highland Society’s Gaelic Dictionary. This great work required very extensive and detailed acquaintance with Celtic literature. The materials which passed into his hands from those of Ewen Maclachlan were not scanty but were as yet unarranged when death removed him. The Dictionary taxed to the utmost the time and strength of a man who never shrunk from toil and it was completed in a way which left little to be desired.

In consideration of the great learning demonstrated in this work he received, soon after its completion, the degree of Doctor of Laws.

Dr Mackay’s conversion took place before the period of his college life. He did not leave his home in the far North without the fear of God in his heart. He knew the gospel before he was licensed to preach it. His ministry at Laggan was not fruitless. The Lord was with him from the outset, and the gospel which he preached was with power. But amid his literary labours, and in the society of those with whom he came in contact in gathering materials for his dictionary, his zeal began to wane, and his soul withered under a spiritual blight. But his backsliding was healed, and the love and joy of earlier days came back again before his brief ministry at Laggan was closed.

He himself thus described to the writer the means of his recovery. On a communion Sabbath, while he was seated at the Lord’s table, the minister who was addressing the communicants spoke of the guilt and danger, and of the course and causes, of backsliding. Beginning with a soul’s first movement from the mercy seat, he described with such minuteness the whole course of his declension that he felt as if every eye in the congregation must have been fixed on him, so thoroughly did he find himself exposed before them. Venturing to look up, he saw every eye fastened, not on him, but on the speaker, who, after describing his very case, passed on to speak of the remedy and to commend to the guilty backslider the merits of atoning blood, the riches of forgiving mercy and the power of renewing grace. The Word came to his heart with power and, before he rose from that table, he cast himself at the feet of Jesus in the hope of mercy and, with brokenness of heart and without reserve, surrendered himself anew to the Lord.

In 1831 he was translated to Dunoon. The charge of Logierait was offered to him at the same time, but he chose the more arduous post. In the restored fervour of his first love, he devoted himself to the duties required of him as minister of Dunoon. The territory embraced in his charge was wide, for the parishes of Dunoon and Kilmun had been united to form it. Even he could not, without an assistant, overtake the necessary pastoral work. At Kilmun there was a church in which the minister of Dunoon must occasionally preach, and beyond Kilmun lay the district of Ardentinny, while on the other side of Dunoon was the district of Toward. During his ministry, summer visitors began to resort to all these places. And to provide the stated supply of preaching at each station, Dr Mackay laboured till churches were built at both Toward and Ardentinny, a new parish church erected at Dunoon, and the church at Kilmun repaired. In course of time he secured the aid of three assistants. He successfully accomplished the great labour of collecting funds for these objects.

After 1843, the same kind of work had to be repeated in connection with the Free Church. During the year from 1 May 1835 he travelled 1577 miles, within the bounds of his own charge, visiting and catechising his people and holding meetings for prayer and exhortation. The record of that year shows no exceptional amount of work; it furnishes but a sample of the regular course of his labour during the earlier period of his ministry at Dunoon. In course of time he was called to preach in other places with increasing frequency, till in 1843 his fragmentary diary shows that in five months he preached 77 times and in 25 places beyond his own charge; and during 1845, 169 times and in 47 places.

Amidst the bustle of Disruption times his labour was excessive. He travelled over almost all the Highlands and Islands preaching the gospel, explaining the causes of the Disruption, and organising congregations in connection with the Free Church. Most uncomplaining was he during all that arduous toil. The ready response of the Highlanders to the call to separate from Erastianism, while carrying with them in their hearts the principle of national religion, was to him ample reward for all his wearying and wasting labour. To him, a Christian Highlander, this was solace most refreshing. The cause of Christ was prized, and the Highlanders were not dishonoured, and he was therefore glad. His joy bore him through toils which would have seemed impossible to a less resolute man.

Most befitting was his appointment as Convener of the Free Church Assembly’s Committee on the Highlands. No man loved the Highlanders with a deeper love, and no Christian was more anxious for their spiritual welfare. Labour for their good he counted no toil. He did not shrink when he looked forward to it, and he did not care to speak of it when it was past. The amount of correspondence, conference and toilsome travelling which he undertook, in furtherance of his schemes for the benefit of the Highlands, is almost incredible.

There are men who will not work unless they can climb to some housetop to proclaim what they are doing, and to tell what they have done. But Dr Mackay’s heart was set on doing work and reaping fruit; he could not endure fuss. To other eyes his schemes sometimes seemed Utopian; and in prosecuting them he was regarded as intolerant by those who stood aloof and objected when they should have sympathised and aided. His aim was single, and he was willing to “be spent” in labouring to attain his object. It was to him no recommendation of a scheme that it could be easily carried out. He would fain fill his consciousness with labour when his heart was set upon an object, and the prospect of toil was to him rather a stimulus than a bugbear. “Our friend Mackay,” Mr Monteith of Ascog once said, “has a horror of short cuts.”

In 1849 he was appointed Moderator of the General Assembly. His appearance and manner suited the position, and his addresses were such as to delight his friends. The most powerful speech he ever delivered was one which he addressed to that Assembly. Stepping down from the chair, he took up his position, as Convener of the Highland Committee, beside the clerk’s table.

With rare power, and sometimes with thrilling eloquence, he pled for a more generous consideration of the needs of the Highlands. The fervour of a Scot, the fire of a Highlander and the zeal of a Christian combined their forces in the power that bore him onward in the course of his eloquent pleading. There were many in the house who, till then, did not know what Dr Mackay could do, and many then discovered for the first time how much was covered by his unobtrusive demeanour.

It seemed a strange way of showing his interest in the Highlands to forsake for a season his native land and transfer his labours, as a minister, to Australia. It looked like an abandoning of schemes which he alone had started and which only he seemed fitted to promote. But his going to Australia was the crowning proof of his deep love for his countrymen. He was ever prone to be sanguine. Unlikelihoods only roused him to exertion. He thought all Highlanders who were amassing wealth in Australia would be ready to contribute to the support of the gospel in their native land. He expected to gather them into communities in the land of their adoption and to enlist their sympathies in behalf of the cause which he himself had so much at heart. He did not adequately take into account the power which “the love of money” has over men – how it can close their hearts and hands and purses against the claims of the gospel.

But his leading conscious aim was to secure a supply of the means of grace to the Highlanders, whom oppression had driven, and whom gold had drawn, from their native land. He accordingly brought the case of the Highlanders in Australia before the Colonial Committee and the General Assembly in 1852, suggesting the propriety of sending out a deputation to labour among them, and expressing his willingness to go if required. The Colonial Committee, on the recommendation of the Assembly, accepted the offer of his service, and appointed him a deputy to Australia. He at once resigned his charge at Dunoon and started for the colony.

In April 1854 he was inducted as minister of the Gaelic congregation in Melbourne, where he laboured for two years. He was in his sixty-first year when he landed in the colony; but during the first 12 months of his ministry there, he preached 146 times and travelled 3081 miles, searching out and addressing the scattered Highlanders, besides ministering to the people of his charge in the great colonial city. In 1856 he removed to Sydney and became minister of St George’s Church in that city. Leaving with his congregation at Melbourne an effective organisation and a handsome church, he undertook to provide both for his new charge at Sydney. In 1858 he came to Scotland to collect funds for his new church, and as a deputy to the General Assembly of the Free Church. Returning in 1859, he resumed his work at Sydney and, with his wonted zeal and diligence, continued to labour there till his final return to his native land in 1862.

Not long after, he was settled in Tarbert, Harris, as minister of the Free Church congregation in that remote locality, and laboured on till failing strength compelled him to resign his charge. During the last year of his life he resided at Portobello, his interest in all that bore on the Redeemer’s cause still unabated. But feeling that he had outlived the generation that knew him, he looked regretfully on the departed brightness of other days, and anxiously towards the darkening prospect in the future.

His last illness was sudden. It seized him on his journey homeward from a meeting of the Synod of Glenelg, of which he was still a member. His bodily strength was shattered, and his mental vigour greatly weakened by the attack; but amidst the delirium of fever, and during intervals of wakefulness and pain, one object alone was in his view. He fixed his eye on Jesus and sang of His beauty. He looked to “the land that is afar off” and pined to be in it, till his Saviour came for him and his ransomed spirit was borne to the rest for which he longed. He died on l7 May 1873.

His success as a preacher won for him his grave in that beautiful spot in which they bury their dead at Duddingston. A sister died not long before himself. Feeble and downcast, and at a loss to find a grave in which to bury his dead, he went forth in search of one. As he walked sadly along the road, he met a gentleman who accosted him and, learning the object of his quest, at once kindly offered him a burying place. There, after the interment of his sister’s remains, a grave would be reserved for himself. The reason he assigned for his kindness was his recollection of a sermon which he heard the doctor preach about 35 years before in the church of Duddingston and which the preacher himself had quite forgotten. The text was remembered, and the leading ideas of the sermon, and the casual meeting renewed the impression made by the sermon when it came from the preacher’s lips. On referring to his notes, Dr Mackay found that on the very day so marked in the memory of the other, and from the very text he mentioned, he had preached just such a sermon as had been described.

Dr Mackay’s personal appearance was remarkable. Tall, with a handsome face and figure and a dignified bearing, no one could look on him without feeling that he was no ordinary man. He was extremely reserved. He never opened up his heart but to a friend, and was far from ready to open even his mouth to any other. No one was allowed to know him fully whom he could not fully trust. A reticence made him sometimes seem austere, but no man could be more genial and entertaining when there was an attraction to draw him out. He shone in conversation only when in earnest or at ease. His mental resources were great, but he did not care to shew his wares in his window. Always careful to have his own mind rightly informed about every subject on which he spoke, he lacked the power to present it vividly and pithily to others. In an address, he went over again all the ground he traversed in his thinking. Instead of the results, he gave the process of his study. This always made his sermons and his speeches lengthy. His train of thought was always in exact logical sequence, and he was always ready, without effort, to clothe his thinking with correct expression; but a redundancy of words concealed his power. Only when he spoke under the impulse of strong feeling could his hearers feel the force of his thinking. His words seemed fewer then because they were more rapidly uttered, and the thought seemed then to bear a fairer proportion to the speech.

His preaching was always edifying. As a systematic divine, he was accomplished and exact; but his preaching was not distinctively dogmatic. He was quite as anxious to indicate the fruits of the truth, as applied, as to unfold the treasures of the truth as revealed. Careful to distinguish a life of godliness from all counterfeits, he was wont to deal closely and searchingly with the consciences of his hearers. He followed the bearing of truth down to the everyday life of men as surely as he traced up its wonders to the counsels of Jehovah. And yet he was not a specially practical preacher. All the necessary elements were found in his teaching, and none of them in preponderance. To an intelligent and earnest hearer he was always interesting, and not infrequently he arrested the attention of all classes of his hearers by the earnestness of his manner and the eloquence of his words. But, best of all, he was a praying preacher. With a self-abasing sense of his own unfitness for the service of the gospel, he leant his weakness on Him whom he preached; and the power of God, in answer to his cry of faith, wrought revivingly in the hearts of the living, and raised not a few of the dead “into newness of life”.

John Kennedy.

Taken, with slight editing, from Disruption Worthies of the Highlands; tributes from a presbytery and synod have been omitted.

———————————————————————–

Dr. Mackintosh Mackay, Harris

From: The The Free Church of Scotland Monthly Record of September 1873, p.191

Dr. Mackay was a native of the county of Sutherland, having been born at Duartbeg (Eddrachillis, we suppose) on the 15th November 1793. His father, Mr. Alexander Mackay, had served as a lieutenant in the North Lowland Fencibles; and his mother was a daughter of the Rev. Mr. Falconer, minister at Badcoll. Their family of sons and daughters had been trained in the way they should go, and all served their generation, by the will of God, in respectable stations; and with the exception of two sisters, who still survive — one at Portobello, and another married in Australia — all entered into rest.

Before leaving his father’s house to prosecute his studies, Dr. Mackay called for the wise and venerable William Calder, Catechist, and was addressed by him in the words of David — “And thou, Solomon, my son, know thou the God of thy father, and serve him with a perfect heart and with a willing mind: for the Lord searcheth all hearts, and understandeth all the imaginations of the thoughts: if thou seek him, he will be found of thee; but if thou forsake him, he will cast thee off for ever. Take heed now; for the Lord hath chosen to build an house for the sanctuary: be strong, and do it.” The words thus addressed to the student’s youthful ear by an eminent man of God, appear to have been spoken to his heart, and to have been the key-note to his future life. A word fitly spoken, how good is it!

Dr. Mackay studied at St. Andrews, having been presented to the Mackay Bursary there by Lord Reay; and he continued throughout life to enjoy and highly to appreciate the respect and esteem of the succeeding and of the present Lord Reay, and of all the members of that noble family.

It may serve to show our young students their superior advantages, if we inform them that Dr. Mackay walked all the way from Sutherland to St. Andrews before entering college there. Dr. John Hunter was the Professor of Humanity, and under that accomplished scholar the young student applied to his work with a will; and, we believe, the thoroughness with which he then learned to do his tasks characterized him in all his classes, and, indeed, in all his after labours and works. However numerous and varied the demands upon his time and attention, he did nothing by halves. His known proficiency as a Celtic scholar procured his being employed by the Highland Society to compile their Gaelic Dictionary. This was a work of immense labour, and the Doctor was known to add to his hours of toil by taking a cold bath when sleep would have been the more pleasant, because the more needed, relaxation. His engagement in this great work brought him into acquaintance with Sir Walter Scott and other literary celebrities, and on its completion the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws was conferred upon him.

In 1823 he was licensed to preach the gospel; and in 1825 ordained minister of Laggan, in the heart of the Highlands, and amidst scenery of much natural beauty, in the neighbourhood of which the Queen passed a season some years ago. In 1832 the Doctor was translated to Dunoon, and was honoured with much usefulness in that parish, and with much respect from the numerous visitors from Glasgow and other places that passed their summer months on the banks of the Clyde. He took an active and decided part in the Ten Years’ Conflict, and was one of thirty-two ministers who signed the circular calling the Convocation in 1842. Of these there were only two survivors two years ago. When the Disruption took place, it may be truly said that the care of all the churches in the Highlands devolved on Dr. Mackay. The amount of work which he did (1) in the way of correspondence with ministers, probationers, and vacant congregations, as to supplies; (2) in going in the schooner Breadalbane from place to place preaching on Sabbath and week days; and (3) in editing and writing for the Gaelic Witness, implied an amount of labour which could not have been undertaken by any other man; and the only satisfactory explanation of his abundant services was that it was not he, but the grace of God in him.

On the occurrence of the potato failure in 1846-7, when famine began to be not only feared, but felt throughout the Highlands, Dr. Mackay was the first to ask a collection from his own congregation at Dunoon, and to appeal to his church and country to come to the rescue; and £15,000 sterling was the liberal and serviceable response.

Soon after, during the sitting of the General Assembly, Dr. Mackay met a select number of ladies and gentlemen, who organized the Ladies’ Association for promoting Education in the Highlands and Islands — an association which has done immense service to the Highlands, and with which the names of Miss Abercrombie, Miss Cowan, Dr. McLauchlan, and a host of others, will long be honourably mentioned and remembered. Besides this, he had previously originated a Synod Bursary in the Synod of Argyll, which has aided many students in prosecuting their studies for the ministry, and which we hope is still destined to do good work in that good cause.

In 1849, Dr. Mackay was chosen to be Moderator of the Free Church General Assembly; and when retiring from that office, which he filled with credit, he preached an able and excellent discourse — which was published soon after — from Ps. 148;14 — “He also exalteth the horn of his people, the praise of all his saints; even of the children of Israel, a people near unto him. Praise ye the Lord.” Among the Doctor’s great services to the Free Church in the Highlands, his originating and arranging a scheme for the payment in full of all debts upon churches and manses deserves to be specially noticed. He called a meeting of the Church’s ablest and most liberal members, which was attended only by three gentlemen — Mr. Campbell of Tilliechewan, Mr. McFie, Greenock, and Mr. James Cunningham, Edinburgh. Each of these subscribed £1000, and Mr. Cunningham gave his able and efficient services in working the scheme; and so by giving one-half or thereby of the whole debt, on condition that the remaining half should be raised locally and the whole debt discharged, the thing was done, to the great relief of many ministers, and the lasting benefit of their congregations. Aid was, of course, obtained from other parties, in addition to the £3000 so generously given, as above stated.

Dr. Mackay and Dr. Cairns went to Australia in 1853, after being loosed and set apart for the work of the Lord in that colony by the General Assembly. Dr. Mackay was then in the sixtieth year of his age, and, as appeared to some of his friends, “too old a tree to transplant.” But he himself had the spirit and ardour of youth; and he hoped in various ways to be of service to his countrymen who had already emigrated to that country, and he contemplated organizing methods to induce and assist others to emigrate in greater numbers. He did good work in Melbourne and Sydney, but his efforts were not seconded as he would require; and from various causes, doubtless including increasing infirmity, the Doctor returned to his native country, and was settled as minister of Harris.

Finding himself unable to do the work requisite in that charge, he procured the appointment of a colleague and successor, to whom he gave up the manse and whole emoluments, retaining his status as a minister and member of Presbytery, and his income from the Aged and Infirm and Pre-Disruption Ministers’ Funds.

His last public work was to attend the Synod of Glenelg on the 9th April. He was opposed to union with the United Presbyterian Church, but is reported to have said that he trembled at the idea of a second Disruption. In Australia, Dr. Mackay favoured the union which took place there, believing it a right thing to do in the circumstances in which the Presbyterian Churches are there placed. But he considered the state of the Churches at home so far different as to oppose the majority.

Besides the Gaelic Dictionary, which was his great literary work, and editing an edition of Rob Donn’s poems, published at Inverness, Dr. Mackay found more congenial work in publishing a volume of sermons on the Christian Warfare, and two volumes on the Beatitudes, besides funeral sermons on the occasion of the death of his esteemed friend, the Rev. Roderick McLeod of Snizort, and the burial of the honourable Mrs. Aylmer in the family vaults at Tongue. By these works he desired and deserved to be long and honourably remembered, and in them, though dead, he yet speaketh, as an able minister of the New Testament — a workman not needing to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth.

In the Glasgow Assembly in 1843, as sites for churches and schools were then refused by the Duke of Sutherland, Dr. Mackay called the attention of the Assembly to that subject, and his speech was characterized as the speech at that Assembly. This was no faint praise. In the year 1845 he appeared at the bar of the General Assembly to plead for the translation of Mr. William McKenzie, Tongue, to Breadalbane; and Mr. Handyside pronounced his speech the best and most powerful pleading to which he had ever listened from the bar.

But all flesh is as grass; and ministers, however able and eminent, continue not, by reason of death. They rest from their labours, and their works do follow them.

Dr. Mackay married in early life, and the issue was one child, who died in infancy. The widow survives to mourn his loss.

Much might be added to all that is said above from personal knowledge of the subject of this notice — as a gentleman of cultivated feelings and taste, a scholar of varied attainments, a valued friend, a true patriot, and an upright man of God. In looking over his voluminous correspondence, it appears that while he had asked and obtained many favours for others, there was no trace of asking favours for himself. He was one of the most large-hearted and unselfish of men.

Rev. John Mackay, Lybster